Art In The Fort

Fort Kochi has emerged as an important destination for lovers of art and culture. A visit to the Kochi–Muziris Biennale can be a prized experience

Sue Williamson’s ‘One Hundred and Nineteen Deeds of Sale’ at Aspinwall House. All photos courtesy: Kochi Biennale Foundation.

Sue Williamson’s ‘One Hundred and Nineteen Deeds of Sale’ at Aspinwall House. All photos courtesy: Kochi Biennale Foundation.

When artist Sue Williamson visited Fort Kochi in 2017, she was struck by the similarities of the colonial histories between the place and Cape Town, where she lived. Back in South Africa, she discovered transaction records at the Cape Town Deeds Office that chronicle the enslavement of Indians who were brought there by the Dutch East India Company to work in estates and gardens in the 17th century. For the fourth edition of the Kochi–Muziris Biennale (KMB), Williamson has inscribed white T-shirts with the little information she found in the archives—the name given by the master and the slave’s age, gender and place of birth. These T-shirts that Williamson calls ‘One Hundred and Nineteen Deeds of Sale’ flutter on a clothesline at the edge of Aspinwall House, overlooking a picturesque Arabian Sea. It’s a stirring reminder of what displacement means, so very unlike all the tourists who have flocked from all over the world to see the biennale.

Fort Kochi, off the coast of Kerala in south India, was always on the radar of international tourists. It is part of Kochi, a natural harbour, that was fought for and won by three colonizers—the Portuguese, the Dutch and the English. Not to mention the varied cultures—the Chinese, Israelis and Arabs—that made it their home. From the writings of the Frenchman Jean-Baptiste Tavernier to China’s Ma Huan, Fort Kochi finds mention in several pre-modern texts by explorers, stoking the curiosity of the discerning traveller. The Chinese fishing nets that dot the shore and the St Francis Church where Vasco da Gama was first buried are all testament to history that is strewn around, accessible without effort, inspiring artists like Williamson.

Aspinwall House, the main venue of the Kochi-Muziris Biennale

Aspinwall House, the main venue of the Kochi-Muziris Biennale

Aspinwall House, the biennale’s main location, for instance, is a compound consisting of offices, a residential bungalow and some warehouses, built in 1867 by the English trader John H. Aspinwall. Another venue, Anand Warehouse, on the other hand, is an active spice warehouse situated on the bustling Bazaar Road. Each space has its own character, its personality rubs off on the artworks exhibited there.

In 2016, when I had travelled to Kochi for the third edition of the biennale, I had just discovered I was pregnant. I remember walking through Raul Zurita’s ‘Sea of Pain’. The Chilean poet had dedicated his installation to Galip Kurdi, the brother of Alan Kurdi, the three-year-old boy whose image of being washed ashore a Turkish beach became a bleak symbol of the Syrian refugee crisis. Galip, Alan and their mother Rehan drowned in the Mediterranean Sea while trying to escape Syria. Zurita filled a large hall in Aspinwall House with almost knee-deep seawater. You had to walk through it to be able to read the poet’s questions written on the wall. He asks, “Don’t you hear me? In the sea of pain”. “Don’t you see me? In the sea of pain”. When you reached the other side, you were confronted with a final statement by Zurita, “I’m not his father, but Galip Kurdi is my son”. I remember being unable to hold back my tears as I imagined what it must mean for parents everywhere in the world to have to make such terrible choices for their children. The biennale, perhaps, has always been about displacement.

For this edition, too, we’ve come to Fort Kochi at about the same time as two years ago. The curled-up human that was inside me is now a toddler, eager to free her hand from mine and experience some art. She doesn’t talk as yet but I am sure that her favourite work was Temsuyanger Longkumer’s ‘Catch a Rainbow II’. The work, installed at Pepper House, consisted of overhead sprinklers that came on every few minutes, cooling everyone standing under it. (Winter in Kerala is non-existent, with the temperature always hovering around 33º Celsius.) The misty drizzle gave rise to a low rainbow, inspiring children, including mine, to try to catch it.

“It’s all destiny in some ways,” says Bose Krishnamachari, who co-founded the biennale with fellow artist Riyas Komu. Krishnamachari, who is originally from Kochi, occasionally curated exhibitions mainly showcasing works of other artists from Kerala. In 2010, at a casual dinner, the then minister for education and culture, M. A. Baby expressed his interest in promoting visual art in Kerala. “The state has the finest film festival (the International Film Festival of Kerala, held in Thiruvananthapuram) and theatre festival (International Theatre Festival of Kerala, held in Thrissur). We wanted to do something similar for visual arts,” says Krishnamachari.

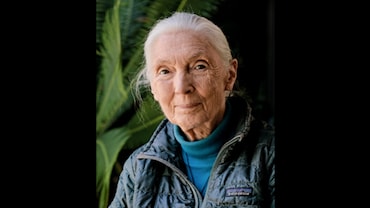

KMB curator Anita Dube with KMB president Bose Krishnamchari

KMB curator Anita Dube with KMB president Bose Krishnamchari

Between that dinner and 12 December 2012, when the first edition of the biennale was inaugurated, Krishnamachari and Komu were mired in controversies. The leftist state government questioned not just their sometimes extravagant spending (they spent Rs 2 crore on the renovation of the Durbar Hall, out of the Rs 5 crore given by the state) but also the very need for the government to be involved with and sponsor such an event. But the two men weathered every storm and went about garnering support from the largely Mumbai- and Delhi-based Indian art fraternity and from like-minded bureaucrats. That they had to pawn their wives’ jewellery to fund the biennale is a tale that has been oft repeated.

Within a short span of time, the biennale has made a name for itself. At the recent art fair in Basel, Zoe Butt, curator for the 2019 Sharjah Biennale, called KMB one of the most important art exhibitions of our time. But Krishnamachari and others involved with the event seem to understand that praise from the elitist and niche world of art does not translate into a successful and, more importantly, sustainable biennale if the residents of Kochi don’t feel invested. “In the first edition, we printed and distributed pamphlets to everyone explaining what a biennale is,” says Krishnamachari. Every year the Kochi Biennale Foundation makes more and more efforts to reach out to the public—from talks to movie screenings to organizing local rituals such as burning the effigy of an old man called Pappanji on New Year’s Eve to celebrate the passing of a year.

Malaysian art collective Pangrok Sulap unveiling their woodcut print

Malaysian art collective Pangrok Sulap unveiling their woodcut print

Last year, in the monsoons, parts of Kerala experienced devastating floods. While Fort Kochi was not affected physically, all industry took a hit along with the rest of the state. Tourism, apart from agriculture, is a major source of income for Kerala. “Almost no tourists came for about two months during and after the floods,” says Biju Bernard, who runs the Master’s Art Café in Fort Kochi.

Our homestay, Kapithan’s Inn, was two doors away from Biju’s café on Bernard Master Road, named after Biju’s father, an educator and local historian. This is where we turned up most days for breakfast. The café is similar to the many that have emerged in the area over the past decade. It’s a family-run enterprise—the husband waits on tables, the wife cooks. Tou-rists wait patiently as each dish comes out of the kitchen freshly prepared with love and care. After a few angsty, tantrum-filled meals, we realized that had we informed our host of the order for the little one, it would always appear promptly within minutes.

‘Water Temple’ by the Chinese artist Song Dong, at Aspinwall House in Fort Kochi

‘Water Temple’ by the Chinese artist Song Dong, at Aspinwall House in Fort Kochi

In her concept note, this edition’s curator Anita Dube, an acclaimed artist herself, writes about going back to the “warm solidarities of community; that place of embrace where we can enjoy our intelligence and beauty with others, where we can love; a place where we don’t need the ‘other’ as an enemy to feel connected”. It’s easy to see what she means when we look at a work like ‘Water Temple’ by the Chinese artist Song Dong. The installation consists of an open-roof, circular glass structure, lined inside with bowls of water and paint brushes. A steady stream of ‘pilgrims’ paints on the glass surface with water—the setting sun, swaying coconut trees, boats; scenes that vanish as poetically as they appeared. There’s enthusiasm and concentration and finally a sense of calm. “It’s a work that exemplifies what I’m trying to do with this edition. It is about making connections; with the artwork and each other,” says Dube, who had the added responsibility of pulling off the biennale despite major delays due to the floods. “We needed to make that extra effort to help Kerala’s economy limp back, and infuse enthusiasm in the locals who have lost so much,” she says.

It’s also easy to experience warm solidarities when you are on vacation. Like the time when Bernard picked up my crying toddler, put on some music and waltzed with her in his arms as I sipped my coffee and cut into a banana pancake.

TRAVEL TIPS

The Kochi–Muziris Biennale is on till 29 March 2019. The nearest airport, Cochin International Airport, is about 40 km away from Fort Kochi.

- Clean, comfortable homestays are aplenty in the area and can be booked through sites such as booking.com. Many also offer tour services, including houseboat cruises.

- A great place to dine while you catch up on art is the Kashi Art Café, a venue of the biennale.

- Don’t miss out on local monuments such as the Mattancherry Palace, known for its murals; the Pardesi Synagogue, originally built in 1568; and the Indo-Portuguese Museum that contains the oldest relics of India’s catholic community.