- HOME

- /

- True Stories

- /

- Heroes

- /

Rescuing Syria's Saviours

Inside the daring international operation to bring Syria’s famed White Helmets to safety

White Helmets volunteer Khaled Najim rescues a little girl in Khan Sheikhon, Idlib, Syria in February 2019. (Photo courtesy White Helmets)

White Helmets volunteer Khaled Najim rescues a little girl in Khan Sheikhon, Idlib, Syria in February 2019. (Photo courtesy White Helmets)

It was black as pitch on the Syrian side of the border and floodlit on the Israeli side when the curtain rose on a dramatic rescue. Out of the darkness in the Golan Heights they came— the famed Syrian White Helmets—the bankers and barbers and ordinary citizens, known across the world for their courage. They came, exhausted and frightened, walking with their families up the grassy slope in Syria towards the forbidden border with Israel.

Over the course of Syria’s seven-year civil war, these men and women of the Syrian Civil Defence Force had braved barrel bombings and chemical attacks to save more than 1,14,000 citizens who dared oppose President Bashar al-Assad. Now, singled out for torture and death by the regime, they had to be rescued.

In the fall of 2012, Bashar al-Assad’s government began attacking villages, towns and cities that were against his regime. His claim: Any opposition to his autocratic rule was an act of terrorism. He withdrew all ambulance, fire and rescue services from areas not under government control, leaving citizens helpless. As bombs fell, there was no one to put out fires or help people trapped in the rubble. And when the attacks ended, there was no one to restart the electricity, reconnect water services or repair bridges.

That’s when groups of ordinary Syrians, first in the cities of Aleppo and Idlib and later throughout the rebel-held areas, united to respond.

After receiving training from Mayday Rescue, a UK not-for-profit foundation in Jordan, and with funding from Canada, the United Kingdom, Germany, the United States, Japan and the Netherlands, what began as the Syrian Civil Defence Force had, by 2014, morphed into a movement of 4,200 volunteers. They worked in approximately 150 rebel towns, villages and cities. Because they donned white construction helmets before going to a rescue they came to be called the White Helmets.

Jihad Mahameed, 51, a former accounts manager at a bank in Daraa, remembers the night in January 2013 that he became a White Helmet. “Our neighbourhood was hit with bombs. A woman was injured and crying. She was sure her baby was dead.” Mahameed and his friends began digging in the rubble. “We found the baby, covered in dust and sitting in a corner of the building, looking like she didn’t know what had happened.” Mahameed tucked her into his arms, and the child clung to him until he was able to return her to her mother.

Jihad Mahameed, White Helmet

Jihad Mahameed, White Helmet

Farouq Habib, 37, is the White Helmets’ support-unit director and liaises between the group and Mayday Rescue. Before the bloodbath by Assad’s forces left almost 18,000 dead across the country, he was an investment banker in Homs. Habib saw his house destroyed and his family displaced.

Like Mahameed, Habib was arrested, jailed and tortured for months by the regime. Like Mahameed, he doesn’t talk about that. Instead, he talks about rescue: “When the bombs explode, some people run to escape. Others run to help.”

Armed with stretchers, not guns, the White Helmets became heroes. They also became the public enemy of Bashar al-Assad, in part because they were keeping people alive despite his bombardments, but also because they attached cameras to their helmets to record the chemical attacks and barrel bombings, gathering evidence of his war crimes.

In retaliation, as areas fell to the regime, amnesty was offered to all but the White Helmets. “They were singled out, taken off buses, put into regime detention facilities,” says James Le Mesurier, founder of Mayday Rescue. “They were tortured, terrorized and forced to make video confessions alleging that they had been responsible for conducting atrocities.”

They were also subjected to ‘double tap’ operations: The regime would bomb an area, and when the White Helmets rushed in a second bombardment would target the rescuers. Then, after the fall of the rebel-held areas in the south in June 2018, residents were told they had to fill out reconciliation forms, pledge allegiance to Assad and identify terrorists, mass graves and White Helmets. The first responders feared they would be arrested, tortured and made to disappear. With 255 of their numbers already dead and more than 700 wounded, the risk to their lives was extraordinary.

Farouq Habib, support-unit director for the White Helmets

Farouq Habib, support-unit director for the White Helmets

***

The rescue operation was driven by people in the field, such as special envoy Canadian Robin Wettlaufer. Located in Istanbul, she’d been working with the White Helmets—arranging funding, training and support—for over four years. On 3 July 2018, Ra’ed Saleh, the leader of the White Helmets, met with Wettlaufer and asked, “Is there anything Canada can do to help?” The regime was advancing faster than anticipated; his people were in trouble. The targeted men and women had only weeks, maybe even days to escape.

Wettlaufer dispatched an urgent report to Global Affairs Canada, Wettlaufer dispatched an urgent report to Global Affairs Canada, stating that there was a very real risk that White Helmets could be detained or killed. The response to her message was swift: Yes, there was a responsibility to help.

At the NATO foreign ministers’ summit in Brussels on 11 July, Canada’s minister of foreign affairs, Chrysta Freeland, made an impassioned plea to the assembled foreign ministers. “We have to do something,” she said. “We cannot leave the White Helmets behind. We have a moral obligation to these people.”

If a deal was struck, it had to include resettlement. The United Kingdom, Germany and France responded positively to Freeland’s plea. While the Brussels meeting galvanized the diplomats, politicians and aid workers, time was running out. The threatened White Helmets were on the run, concealing their identities, counting on strangers for clandestine help and staying in touch with Mayday Rescue through coded WhatsApp and text messages.

By now, Assad’s advancing army had closed off the border to Jordan, leaving the Golan Heights as the only crossing point available. Securing Israeli cooperation was paramount, and Jordan had to sign off on receiving the rescued men, women and children from Israel, even if only for a short stay.

As Canada’s ambassador to Israel, Deborah Lyons, notes, “The Israeli government and military put human life ahead of politics and said, ‘We are there to help the White Helmets and to work with the rest of the coalition to get them out safely.’” The White Helmets could transit through the Golan Heights to Jordan.

Now, it was a race against the clock.

On 19 July, Mayday Rescue sent a coded message to the White Helmets: “Head to the border with Israel.” The instruction seemed counter-intuitive—Israel was an enemy border. But it was the only option available. The beleaguered White Helmets began moving from dozens of locations toward the Golan Heights.

The plan was to unlock the gate, receive the White Helmets, process them and load them on to buses bound for Jordan. Representatives of the Jordanian government were there to observe the evacuation, as were UN officials. Mayday Rescue had sent White Helmets Jihad Mahameed and Farouq Habib, each with a satellite phone so the partners could be in touch throughout the evacuation. The two men knew first-hand the danger the White Helmets and their families were in. On this night, they waited for the border to open.

In Amman, the anxiety level at the Mayday Rescue office and the Canadian Embassy in Tel Aviv and the foreign affairs office in Ottawa was palpable. So many things could go wrong. The regime’s military could catch wind of the top-secret rescue, charge the border and attack. Assad could call for an airstrike. Syrian citizens living nearby could seize the opportunity to cross the border when it opened, prompting a military response from the Israelis. The Mayday Rescue office was crowded with envoys, ambassadors, aid workers and UN refugee staff, all awaiting word of the rescue. The room was powered by cigarettes, coffee and anxiety.

“We lost touch with Habib and Mahameed at some points, so the stress escalated,” says Nadera Al-Sukkar of Mayday Rescue. “We also lost contact with the White Helmets. Morale was collapsing. All of us were worried that it’s not going to happen, that it’s too complicated, too difficult.”

The Israeli Defence Force (IDF) had coordinated the time and place where the White Helmets would come across. Just before sundown, they deployed in full battle gear, machine guns shouldered. They set up a table where each evacuee would be identified.

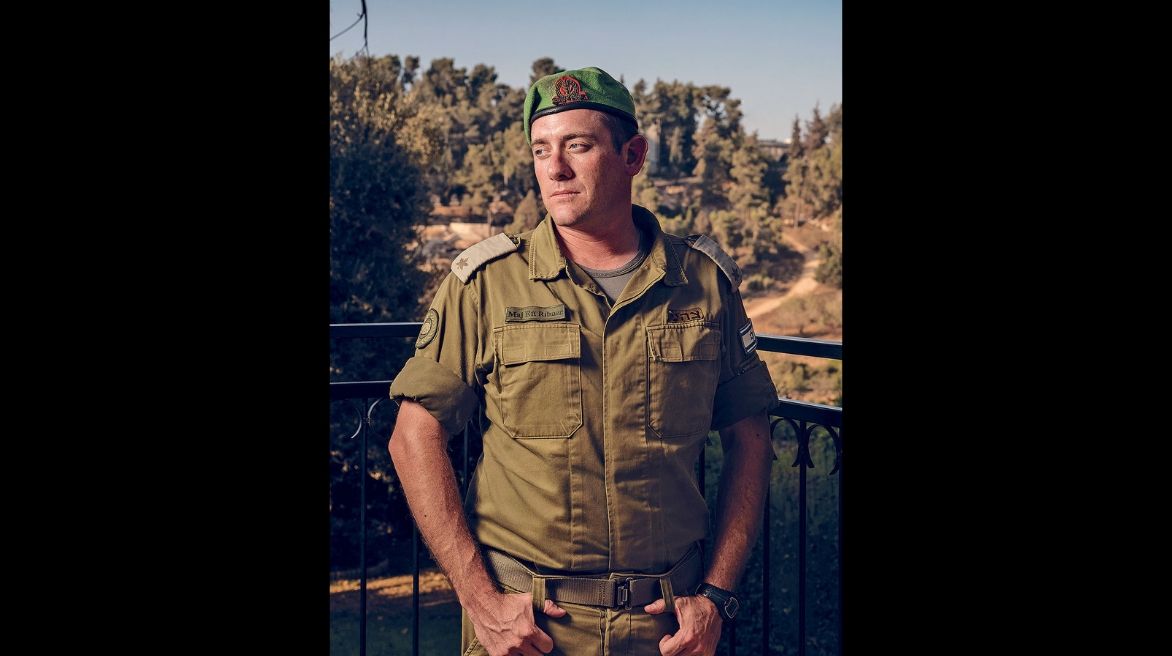

Then shortly after 9 p.m. on 21 July, the IDF gave the order to open the gate between Syria and Israel. As it cranked slowly to a position that exposed the Syrian hills, everyone stared into the dark. Then the IDF’s Major Efi Ribner called the White Helmets to come forward as families—one group at a time. If people were on their own, they were to approach as individuals. The control was tight.

In Amman, those anxiously waiting for word, got the call—an hour later than anticipated. It was Habib. The White Helmets had started to cross. “As the night progressed, it became clear—this just might work,” says Wettlaufer. “But until we found out that the last person was safe, I didn’t relax for a second. No one in that operation centre did.”

Major Efi Ribner, Israeli Defence Forces

Major Efi Ribner, Israeli Defence Forces

***

The night was eerily quiet, except for gunfire in the distance. The White Helmets moved towards the gate.

Habib and Mahameed were the first familiar faces the White Helmets saw. “When the first family crossed, it was an exceptional moment,” Habib recalls, “I had mixed feelings—sadness because this family was forced to leave their homeland but happy because we rescued them.”

The families were in miserable condition—some sick, some barefoot. A pregnant woman had broken her leg, one mother asked if Habib could get milk for her child. A man begged Habib to negotiate safe passage for his wife and children, left behind. There was a newborn baby, delivered two days earlier.

The rescued families rushed to Mahameed, embracing him, asking questions, seeking answers. He hugged them back but discouraged lingering. “I just wanted them safely on the bus,” he says.

At the border crossing, as each family cleared security, they were moved to buses where blankets, food, baby formula and water awaited them. When all 10 buses were filled, they left in a convoy for the Jordanian border. It was 5 a.m. when the last buses arrived in Jordan.

When Nadera Al-Sukkar caught up with the rescued White Helmets at an undisclosed location in Jordan, she realized the enormity of what had been accomplished. In one exemplary initiative, leaders from half a dozen countries had set egos and differences aside in a daring joint effort to save as many White Helmets as was possible.

Out of the approximately 800 White Helmets and family members expected to escape, 422 crossed the border that night.

Robin Wettlaufer, Canada’s head of political affairs for Syria (with James Le Mesurier, founder of Mayday Rescue)

Robin Wettlaufer, Canada’s head of political affairs for Syria (with James Le Mesurier, founder of Mayday Rescue)

“Canada played the leading role in an absolutely extraordinary international rescue operation that came together in a frenetic three-week period,” says Le Mesurier.

The rescuers had been rescued.