Word Sleuth: 10 Terms Every Crime-Fiction Fan Should Know

The crime-fiction vocabulary can be as exciting as the stories themselves

Illustration by Keshav Kapil

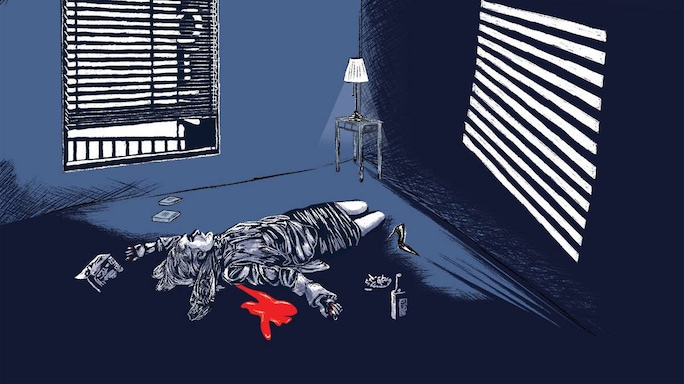

Illustration by Keshav Kapil

Very few things can outmatch the thrill of a bone-chilling, cold-blooded murder mystery, especially on a rainy evening. We dig into the best of crime and detective fiction and unravel vocabulary that brings alive twisted plots and tropes—and help readers understand whodunnit and how.

Crime fiction vs Detective fiction

Crime fiction: A broad overarching genre, it is used to describe any work of fiction that details an act of a crime being committed. It does not necessitate the presence of a detective for its execution—it may even be a fictional autobiography of criminals and their thrilling escapades.

Detective fiction: This is a narrower category with a strong focus on detectives. Irrespective of whether they have been thrust into the role accidentally or not, the detective is expected to expose the guilty party and their evil machinations by the end.

Alibi: Any piece of circumstantial, testimonial evidence or a plot development that directly or accidentally ‘proves’ a particular person was elsewhere at the time of the crime. Often, the culprits are shown to depend on testimonies of the cast to vindicate their innocence, while the detectives must break them down. Think of a culprit who moves the hands of all the clocks in a house to falsify the time of death, or someone who stores a corpse in a freezer and then ‘discovers’ it at a convenient time—estimating the time of death by checking for rigor mortis will be inaccurate and provide the perpetrator an alibi.

Trick: Suppose a group of people see a person plummet to death from the seventh floor of a high-rise, but they see no one else in the balcony. Adding two and two together, they conclude that the person committed suicide. However, they may have failed to notice the wily trick or setup the culprit used to disguise the murder as a suicide. A trick, then, is a crafty, elaborate mechanism that allows a criminal to commit their deeds while fooling investigators and witnesses alike.

Red herring: The criminal understands that the detective is closing in on them. Their escape plans have long failed, and the facade cannot be maintained any longer. As a last resort, they hit upon the devious plan of leaving false, misleading hints that will implicate innocent members of the cast, and allow themselves to make a getaway. These false clues or hints are red herrings. Funnily enough, if an overperceptive detective misinterprets a clue and is led to a wrong solution without the culprit’s interference, it can also qualify as a red herring.

Dying message: A particularly favourite trope among mystery authors, this can take different forms: a scrawl on the floor, a bloodied piece of paper with letters/codes, or the direction in which their fingers point. Dying messages offer various plot possibilities: A murderer may decide to alter the message if they spot it, the investigators may misinterpret it or a character may decide not to reveal the meaning of the message, even if they realize it.

False/fake solution: This is a scenario where detectives show off their knowledge by presenting different solutions to the crime for the readers and the characters—usually all variations except the correct one. While this is usually a humorous trope, in special circumstances, this can be cleverly used by a private eye to lull the criminal into a false sense of security, leading them to make a mistake, leaving damning evidence.

Impossible crime: This is an oxymoron really, since a crime once committed is clearly possible. Yet, it is used to describe an outré crime that, at first glance, seems absolutely impossible. Think of a theft at a bank vault with the latest foolproof anti-burglary traps or a train-jacking case where a compartment disappears between two stations.

Locked room: If an author decides to have a character killed in a room with all the entry points closed, know then that they have been sacrificed at the altar of one of the most fiendish literary devices ever invented. A locked-room scenario (in other words, a hermetically-sealed chamber) is a sinister situation in which a crime is successfully committed at a scene with absolutely no means of entry or egress. The size and scale of the locked room may vary—it could even be an island cut off from the outside world, where it’s evident that only one of the occupants could have committed the crime. Devising a successful locked-room stratagem requires special care, inspired imagination and special attention to detail. No wonder this device has a place of pride among the best crime fiction.

Unreliable narrator: Authors bestow unique powers to this figure—they may distort facts, hide details or manipulate events subtly while maintaining the facade of being an impartial chronicler of all that transpires.

Rule #1: Never trust a narrator unless you want to be nastily shocked later. This trope is rarely used with transparency. Hints about the unreliable nature of a narrator, usually presented in the first person, can appear as imperceptible revelations about their state of mind, the specific words they may have spoken and changed drastically later or even mannerisms, behavioural itches and character traits.

A great example of this is Akutagawa Ryunosuke’s short story In a Bamboo Grove (one of the inspirations behind Akira Kurosawa’s Rashomon) where witnesses provide equally sincere, but contradictory, first-hand accounts of a murder—later dubbed the Rashomon effect. Akutagawa’s story lets readers decide for themselves the authenticity of the incident.