The Call of the Big Blue: Round the World with One Good Leg

An army man with only one leg sets off on a sailboat, driven by his mad ambition to circumnavigate the globe

Illustration by Ashwini Menon

Illustration by Ashwini Menon

There was a muffled crack as my artificial leg snapped. I clutched the railing as the Trishna was flung about in the heaving seas. Suddenly, she rolled violently to one side. Her beam went so deep under water that I thought she would go over completely, but, miraculously, she came up on top again.

The end, I thought, could not be far now. We would all go down, thousands of miles away from home. Perhaps the best thing would be to let sleep take over. Hypothermia and death would soon follow. After all, how could I have imagined that, with just one leg, I could sail around the world?

I had started sailing as an army cadet at the National Defence Academy, Pune. After several national-level regattas, I had even become good at it. Later, I had represented India at several international competitions too. The dream of circumnavigating the globe in a sailboat had seized me in 1978, nearly 10 years earlier, after I had successfully sailed an 18-footer, with two other army officers, from Bandar Abbas, Iran, to Bombay. Indeed, it seemed such a mad ambition that for quite some time I didn’t even tell anyone about it.

But it refused to go away.

Sailing a few thousand kilometres in the Arabian Sea is not the same as circumnavigating the globe.

So how was one to do it? Where would I begin?

Brigadier H.K. ‘Harry’ Kapoor, one of the founding fathers of sailing in the Army, and I met and got down to planning. For a start, I took two suitcases full of books on boat design, construction and ocean sailing, and went off on a 20-day break to Lucknow. The basic fabric of our plan was woven in October and November 1978, over many days and nights of brainstorming.

Early in 1979, the plan was finalized. The crew would consist of 10 army officers, including myself, with six on the boat at any one time. We would buy the vessel in England and sail it to India, thereby gaining valuable ocean-sailing experience. After overhauling the boat thoroughly in Bombay and stocking up supplies, we would head westwards.

Harry put the plan through the usual channels. And then, a long period of waiting began. It took about six years for the approval to come—roughly five times what it took for us to sail around the world!

A lot happened during those six years. Since nobody knew how long the approval would take, I decided to end my bachelorhood. In 1980, I married Asha, a lecturer at a girls’ college in Gwalior.

Then something happened that nearly put an end to all my dreams. In March 1983, while hang-gliding, I smashed into a rock face of a cliff. I fractured my legs, arms and jaw. I was rushed to hospital, where a steel rod was put through my left femur. A fortnight later, that leg developed gas gangrene, and to save my life the leg had to be immediately amputated above the knee.

I was fitted with an artificial leg, pretty rudimentary by today’s standards. How on earth could I, with only one good leg, stand on the wet and slippery deck of a boat as it was tossed about in a stormy sea?

For a while, I must confess, I hit rock bottom. But slowly I recovered. I began the agonizing routine of standing up and walking with prosthesis. When I refused a stick, I was warned that I’d fall. That didn’t bother me. After what I had been through, what was a tumble to the floor? I wrote to Harry that I would be functional by October and was still keen to be considered for the sail round the world.

The official sanction for the voyage finally came through in June 1984. A month later, Colonel T. P. S. Chowdhury, the crew manager, and I flew to England. My job was to select a suitable boat and prepare the ground for the sail back to Bombay, while his was to fix up a few weeks of training for the crew.

I scanned more than 400 boats before settling on the Guinevere of Sussex, an 11-metre-long, fibreglass sloop. Her graceful lines hid a strong and resilient body. She was a soothing sky blue, with a white cabin roof and teak-inlaid decks. To a seaman, she was pure joy.

Guinevere was a little behind in preventive maintenance, so I was able to get her price down to £28,000 [roughly Rs 5–6 lakhs in 1984]—just within our budget.

The other crew members—skipper Major K. S. Rao, Major A. P. Singh, Captains Sanjeev Shekhar and Chandrahas Bharti—flew in, and we began our training in handling an ocean-going boat.

The gods decided to test us on our very first sail. Soon after we set off, headwinds increased to 40 knots [about 75 kmph]. For 15 hours, freezing, soggy and seasick, we sailed in choppy and reef-ridden waters, through a moonless night, negotiating a busy shipping channel.

As gusty winds built up, our English sailing ‘guru’ said, “Someone needs to reef [the process of reducing the area of a sail, usually by folding or rolling one edge of the canvas in on itself] the main sail.”

As if answering a call, I advanced towards the mast on all fours on the wildly jumping wet deck even as I heard someone shout, “A. K. not you.”

“Why not?” I shot back through the howling gale and, bracing against the lifeline holding me to the mast, applied myself to the job. And—gods be praised—I did it!

That first sail proved to be a godsend.

***

I felt a glow of confidence deep inside me. If I could reef the main sail in a storm, I could sail the boat!

Since she was a used boat, lots of repair and maintenance was needed to get Guinevere ready for the passage to Bombay. So after hoisting her out of the water, we set about our work in earnest. We renamed her Trishna, which means a deep-rooted desire to achieve something elusive or unattainable.

The busy weeks before we left for India sped by. Finally, on 12 October, Trishna eased away from her jetty at Gosport, to the martial tunes of an English bagpiper on shore—homeward bound by way of the Suez Canal at last!

We quickly settled down to our routine. Two ‘watches’ of two men each were formed. A ‘watch’ would man the boat, taking turns at sailing her for four hours before handing her over to the next pair. A fifth man would clean the ship, do all the cooking and be on standby. The skipper’s job was to see that all of us did our jobs.

For the first few days at sea, I experimented with various ways to remove and store my limb and my storm-suit so that I could put them back on in the shortest possible time. I ended up keeping the limb on most of the time, even through the night, removing it only during the daytime when I was off watch-duty.

On the evening of 17 October, we heard a radio forecast of bad weather and, soon after, the storm hit. Waves hammered the boat, and at times it tilted by up to 80 degrees. Although the storm soon abated, the swell and chop continued. I even had a piece of cake snatched from my hand by a splashing wave before I could bite into it!

On 31 October, we kept hearing Indira Gandhi’s name on the Spanish and Portuguese radio channels. It was only on approaching Gibraltar that we received BBC bulletins about Mrs Gandhi’s assassination. We sailed into the port with our flags—ours as well as Gibraltar’s—at half-mast.

We stayed in the officer’s mess in Gibraltar and its elementary comforts—a hot bath, wholesome food, a full night’s sleep between clean sheets and a blanket on a real, full-sized bed with the limb off—were gratifying beyond measure.

After a good night’s rest, I awoke to a gentle knock on the door. Moments later, the housekeeper—a plump, middle-aged Spanish lady—entered, and let out a scream. I turned around to find her staring in horror at the limb by the bed. Luckily, she soon figured out it was an artificial limb!

***

After a few stops in the Mediterranean, we passed through the Suez Canal. The southern Red Sea was turbulent all through the 10-day passage to Aden, Yemen, with headwinds, treacherous unmarked reefs, strong adverse currents and busy shipping lanes. Constantly washed over by huge waves, our eyes were hurting and stained red by the salt water. Salt caked the creases of our faces, and lodged deep in our nostrils and throats. Our tongues were swollen, our lips white.

Our appetite vanished—a half-kilo tin of fruit cocktail was often sufficient for the crew of six, with each of us preferring not more than a teaspoon, for fear of throwing up.

At Aden’s Seaman’s Club we washed and cleaned out all the salt from our bodies. We also took a stroll through town to feel what it was like to walk again on land after the rough passage.

Flat and calm seas after we left Aden made me anxious. I wanted us to move fast: Asha was expecting our second baby, due on 10 February.

We were now beginning to receive All India Radio news frequency. That gave us a sense of connectedness in an otherwise disorienting existence.

On 26 January, India’s Republic Day, we dutifully hoisted the tricolour, and five days later, Trishna sailed into Bombay harbour. We were the first Indians to have voyaged all the way home from Europe on a sailboat.

A felicitation was organized a few days after we reached. Asha was in Gwalior. I telephoned her to ask after her health.

Her soft, yet somewhat cold and faraway reply was, “Don’t come, I’ll manage by myself.” I realized then how lonely she was and how selfish I had been.

I caught the next flight to Gwalior. Our second baby girl was born on 9 February 1985.

Soon it was time to begin preparations to sail around the world. But did we really want to?

I told Asha that since I had started this, I had to see it through. If I didn’t, it would haunt me all my life.

Not everyone felt the same way. Finally, four of us—K. S., Bharti, Shekhar and I—formed the permanent crew. Six others—Tipsy, A. P. and four other army officers who had volunteered—Captain Rakesh Bassi, Second Lieutenant Navin Ahuja and Majors Surendra Mathur and Animesh Bhattacharya were to sail roughly a third of the way each, so that, at any point in time, Trishna would be manned by six.

Preparing a boat for a voyage around the world is as much a challenge as the voyage itself! The old army saying ‘The more you sweat in peace, the less you bleed in war’ holds true here too.

Every instrument of Trishna was tested and overhauled. Additional water tanks were installed. The hull was dried out and scraped down; coats of epoxy resin were applied and topped off with anti-fouling paint. A new 100-watt, high frequency radio set was installed.

All vital boat equipment and food stores were stowed in such a way that they could be grabbed quickly even in a dark, upturned vessel. And I got a new limb from the army’s Artificial Limb Centre in Pune.

Finally, on 28 September, Trishna, dressed up in all her colourful flags, was brought alongside the jetty. As I said goodbye to my family I kept thinking: Will I ever see them again?

***

Snapshot of a regular day from the voyage

Snapshot of a regular day from the voyage

The south-west monsoon winds were receding after the rains and during the day, there were gentle winds but before dusk, the sky would darken with forebodings of thunderstorms.

One evening, before dusk, a small, tired bird alighted on Trishna. It was ill so we wrapped it in cloth, and placed it inside a bucket. A large flock of its fellows followed us all night, chirping agitatedly to an occasional feeble cheep from their friend. The next day our birdie died, and we consigned it to the deep blue sea with a heavy heart.

We reached Mauritius on 25 October after midnight. Here, boat and crew were to be readied for the long passage to St Helena, round Cape of Good Hope. Trishna’s water tanks, including the additional tanks we latched on, could carry only 150 American gallons [about 570 litres] of freshwater, which would last us up to 60 days with severe rationing. Some sails needed repairs; all equipment and systems needed looking over.

The first few days out of Mauritius brought light winds. And by the time we neared the Cape, our skipper had ordered strict rationing of freshwater. Two of the water tanks were empty. Brushing teeth and rinsing our mouths were limited to alternate days.

We had barely sailed past Agulhas Point, the southern tip of Africa, when huge seas began building up. The bright sunny sky suddenly became dark, stormy and overcast. Even as we hastily reduced sail, Cape Town Radio’s storm warning for the area came on the air:

“Attention all ships! Winds gusting to 65 knots [120 kmph].”

With all sails down, Trishna was tumbling through colossal seas that rose well over 55 feet high. At times, a wave would break just behind us, and several hundred tons of cold frothing water would threaten to submerge us.

Thankfully, the winds abated the next morning. But it took a while before we were able to relax. A. P. echoed all our feelings when he mumbled, “Something to tell our grandchildren about!”

The sail across the Atlantic up to St Helena, and then to the Caribbean, was quite calm. Having given us a taste of their might, the gods now gave us weeks of safe, pleasant sailing.

One pleasant, windless day, as we were doing about two knots [4 kmph], a whale spouting jets of water appeared barely 150 metres away. It moved straight towards us, its huge black hump above the water. Everyone rushed on deck, life jackets in hand. We tried to start the auxiliary engine in an effort to motor to a safe distance, but then the engine developed a snag. Luckily, we crossed barely 30 to 40 metres ahead of the 12-metre-long creature. Sensing our presence, it executed a fascinating dive. First the hump rose. Then the huge back surfaced, and with a wriggling movement, the whale began its dive. The forked tail, about three metres across, rose and propelled it downwards with a powerful slow-motion flipper action, leaving behind a huge turquoise turbulence. We were to encounter whales many times during our voyage.

***

We anchored off the floating pier of the yacht club in Natal, Brazil, on 28 December. We had taken about a month to cross the Atlantic.

The Brazilian Navy looked after us in Natal. And Shankaran Kutty, one of the few Indians in the area, called us over for a meal. The professor had cooked the meal himself and as we ate, his washing machine choked and coughed over our salty and grimy clothes!

After stops in Suriname and Guyana, we reached Trinidad at the end of January 1986. We were to have our first crew change here and as we approached the jetty at Port of Spain, we could see the tall, handsome Navin Ahuja, Bassi’s replacement and, at 21, the youngest member of the Trishna team.

The first few days after leaving Trinidad brought strong gusting headwinds and opposing currents, and we made almost no progress. When we finally got to Barbados, K. S. got the news of the birth of a daughter. He later named her Trishna.

After the Panama Canal there was a change of crew, with Tipsy Chowdhury, who had been part of the crew on Trishna's first voyage from England to India, replacing A. P.

For the four permanent team members, a crew change was an event to look forward to. The new man always lifted our spirits, and removed the staleness, which tended to set in during voyage.

Tipsy didn’t disappoint us. He brought lots of personal mail and many packets of homemade sweets. He had also brought a set of spare joints for my artificial limb.

The boat had sailed over 30,000 kilometres by now. We dried out seawater from Trishna's fibreglass hull by shoring her up on land for three weeks and overhauled all fittings and instruments.

Our families also visited us. Shekhar’s father came from Varanasi. Asha and Bharti’s wife Manju, flew in together. Their coming did us a lot of good. Alas, after a few days together, back they went.

For the first four days and nights, after entering the Pacific, we inched ahead on windless, glassy seas. At last, a steady breeze sprang up and we reached Santa Cruz, the principal island in the Galapagos. No one here had seen a Sikh with a turban before, and Tipsy was soon nicknamed Ali Baba. One man actually asked him if he was a magician!

Our 5,000-odd-kilometre sail from Santa Cruz to French Polynesia went quickly. Although it was getting cool at night, the days were still clammy below decks and my limb was almost always hot. Pools of sweat collected in the bowl-like lower portion of the socket. I had to clean it out regularly. Also, the steel joints had rusted through; this was a constant source of worry.

On 25 April 1986, Trishna crossed the halfway point of her circumnavigation. From this point on we were headed back home, not away from it.

A fierce three-day storm brewed as we approached Auckland, parting the main sail at the seams with a loud rip. The spare was hoisted, but it, too, blew out in the ferocious gusts.

K. S. and Bharti took turns at mending one of the torn sails. It was tough work, having to put each stitch on the thick sailcloth, threading the needle through the earlier thread holes one by one in the abating storm. They were also repeatedly seasick since any task on choppy seas that demands intense hand-eye coordination greatly increases nausea. But their persistence paid off, and the main sail was hoisted again and, thankfully, the stitches held.

One night, coming up to relieve the port watch, we saw to our horror, a black container ship, a few hundred metres away, bearing down straight at us at full speed. We were inching forward pathetically slowly, right across the huge ship’s bows. It was too late for us to take any avoiding action. On came the ship, its engines pounding. We desperately shone our tiny searchlight in the direction of the ship’s bridge to attract the officer-of-the-watch’s attention.

Our luck held. Suddenly, the ship gave a hard starboard rudder, and veered sharply to the right, still turning as it thundered past barely metres away.

***

A beaming Animesh Bhattacharya was at the jetty in Auckland to greet us. He was to replace Navin. With his loud laughs and backslaps, Bhatta was a welcome addition on board. Earlier, two persons were needed to heave anchor; now Bhatta alone was enough.

A day later, as we headed for Sydney, the barometer began falling sharply. The deep cyclonic low pressure was soon upon us.

And then, what I dreaded most, happened. My artificial limb snapped as I struggled for balance at the wheel. A feeling of utter helplessness overwhelmed me. Boat and crew battled it out. Standing my watch, I crouched, frustrated and despairing, in a cold dark corner of the cockpit, sheltering myself against the stormy spray.

But then, with all my might I fought off my desire to give in.

The storm intensified to a furious head-on 50 knots [93 kmph], with steep 45-feet waves as we tried to make headway. Skipper had gone without sleep for more than 60 hours, and was near collapse when we decided to let Trishna ride out the storm by herself, by securing her heavily reefed sails and rudders to balance out the storm’s fury and hold her as best as possible—a procedure called ‘hove-to’.

As the storm raged, I laboriously cut steel pieces from the spares I was carrying to rivet them to fix the limb. Several unsuccessful attempts and broken rivets later, I managed to stand on my own two feet, although they really were beyond fixing and needed immediate replacement.

On the fifth day the fury abated, and we made good progress towards Sydney. Tipsy was to fly home from there, and Surendra Mathur was to join us. We would miss Tipsy’s infectious optimism.

The prosthetist at Sydney needed around a week to fit me with a new limb, but skipper said we couldn’t wait, so we sailed off after only four days, hoping it would pass the trials at sea!

After the Tasman Sea, not many areas of predictably stormy weather remained. Instead, the danger from reefs, shoals and shipping were to increase greatly on our passage towards Indonesia and the Malacca Straits, and onwards to the Bay of Bengal.

At Singapore, the headmaster of the United World College of South Asia asked me to talk to his students on the travails of sailing around the world on one leg. I spoke instead of its pleasures!

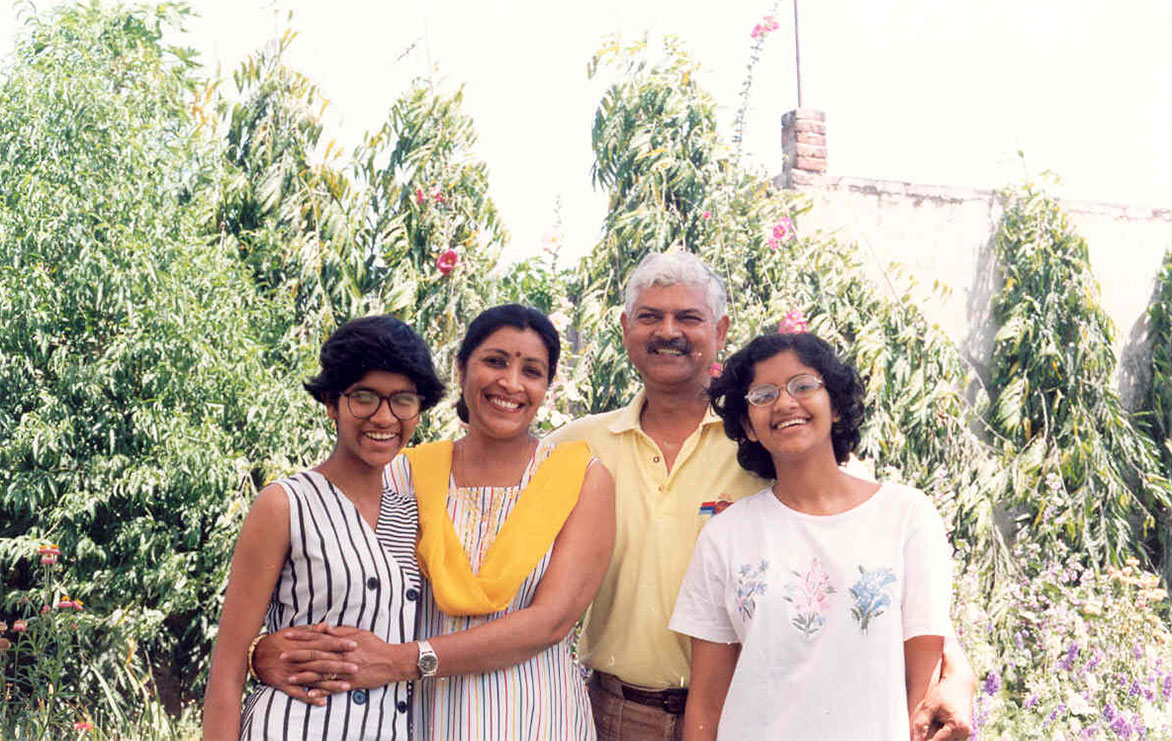

After halts at Penang, the Andamans and Colombo, Trishna sailed into Bombay harbour to a resounding welcome on 10 January 1987. Everything afloat in Bombay feted us home, the ships in harbour jetting water in greeting, shooting flares, blaring horns, and naval helicopters showering us with petals, as we made our way to the Gateway of India where I could see Asha and the girls, dressed in their best and carrying placards, waiting for me.

The author with his family, several years down the line

The author with his family, several years down the line

Trishna then made an overland passage by rail to New Delhi and, as part of the Republic Day parade, ‘sailed’ down Rajpath in a specially fabricated trailer.

I was boarded out of the Army on medical grounds in 1990 and Asha and I moved to Lucknow with our daughters Akshi and Aditi to rebuild life on Civvy Street. I now run a successful petrol pump, administer a school and college that provide low-cost quality education in my village, and run (5K) for social causes whenever I can.

Over 30 years have passed since our voyage, but the memory of it remains as fresh as ever. For me there will never be a boat better than Trishna nor a better crew to sail with than those who sailed her with me.

This is a condensed version of the book Beyond Horizons, published by Rupa Publications; © copyright 2014 by Major A. K. Singh. The text has been printed with permission.