Guardians of the Forest

Prafulla Samantara won the 'Green Nobel' in 2017 for his 12-year legal battle to protect Niyamgiri and its people

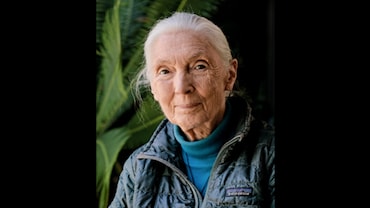

Prafulla Samantara (Photograph by Rajwant Rawat)

Prafulla Samantara (Photograph by Rajwant Rawat)

Rumbling drums and roars of protests suddenly shatter the silence of the verdant Niyamgiri, a hill range in southern Odisha. Word has reached the Dongria Kondh tribes--in the hamlets sprawled across the 250 sq km area--that a mining company is coming to take over their hills. The Dongrias, close to 8,000 in number, Adivasis who have the status of particularly vulnerable tribes, are dangerously close to losing the land they have called their home for centuries. Thousands of men and women march through the dense forests to form a 17-kilometre human chain to physically prevent it. The hills and valleys echo with their rallying cry: "We will die, but not leave our home and our God …"

This moving symbol of peaceful resistance in January 2009 by the Dongria Kondh to protect their habitat from the devastation of bauxite mining reverberated globally. The movement was set in motion in 2003 in response to the UK-based Vedanta Resources Plc signing a memorandum of understanding with the Odisha government (see timeline). Steered by the Niyamgiri Suraksha Samiti (NSS), the movement comprised a number of notable local leaders. Standing with them, often physically, but always morally, is Prafulla Samantara, 66, who took the battle to the Supreme Court and fought until the people won.

A lifelong champion of environmental and social justice, he was awarded the prestigious Goldman Environmental Prize, often referred to as the Green Nobel, this April, for his role in the "… historic 12-year legal battle that affirmed the indigenous Dongria Kondh's land rights" to protect the Niyamgiri Hills from a massive, open-pit aluminium ore mine.

"This movement is the collective effort and sacrifice of many--Adivasis, activists, lawyers. The prize is not mine alone," says Samantara, sitting in his small office in Bhubaneswar's Lohia Academy, from where he runs Lok Shakti Abhiyan (LSA). His warm smile connects him immediately with strangers, but behind the genial, slightly absent-minded demeanour is a steel core that has challenged the might of corporations and governments alike. It is evident that he is deft and purposeful, and often restless to give more of himself to the people and their urgent concerns.

Samantara seems to have little time for himself and his own needs--his life is his work. He has packed it all into a tiny room with a single bed, next to the office space that visitors frequent all day. His wife Usha Rani Acharya is a retired professor of zoology and lives in Berhampur, about 170 kilometres away. His only daughter Sushree Sangeeta, who has a doctorate in ecology, is currently in the US with her husband. Samantara is either on the move--travelling to distant villages or connecting with leaders of the National Alliance of People's Movements (NAPM) in different parts of India-or at his desk, spilling over with books and papers. A large picture of his mentor, the late Rabi Ray, socialist leader from Odisha and former Lok Sabha speaker, faces him.

Samantara had jumped into public life as a student activist: Opposing the Emergency in 1975, as a part of Jayaprakash Narayan's movement, he was sent to jail for a year. "I was suddenly arrested as I was returning to my college hostel after law class," he recalls. Later that year, he discarded the holy thread Brahmins are meant to wear--a bold step for a young man from a small village where untouchability and feudalism ruled. Born in a farmer's family, he was the eldest of six children. His parents encouraged him to study and use his college education, in economics and law, to look after the family. But Samantara's calling lay elsewhere.

The lush forests of Niyamgiri, their beauty and silence, wrap within them life that is at once vibrant and fragile: Leopards, tigers and elephants roam the jungles, in the dense greenery thrive 300 species of rare plants. The rivers Vansadhara and Nagabali, and the numerous springs that dance along the slopes are born here. Every monsoon the hills, with porous bauxite hidden below, soak in rainwater; after the rain stops fountains of water gush forth from the hillsides.

Niyamgiri encompasses the Kalahandi and Rayagada districts, where the Dongria Kondh live as one with nature. They worship the pristine hills, its abundance and pay obeisance to Niyam Raja for the gifts of water, forest produce and medicinal plants. They believe He protects them from the world outside that they are neither exposed to nor understand.

Samantara first heard the rumblings of discontent as the news of a public hearing at Lanjigarh reached him in 2003. By then he was a seasoned environmental campaigner at the forefront of movements against two major projects: a steel plant on the Gopalpur coast that seemed to violate pollution norms and a potentially toxic alumina plant in Kashipur.

Samantara's research during the anti-bauxite movement revealed to him the devastation that a refinery and open-cast mining could leave in its wake--drying up water sources, destroying the green cover and rich biodiversity and shattering the peace of the hills with the drilling, blasting and crushing. The health impact on the people could be grave (skin ulcers, severe pulmonary disorders and, in extreme cases, malignancy) from metal poisoning.

Sensing the shocking indifference of the establishment, Samantara filed a petition in November 2004 to the Central Empowered Committee (CEC), a monitoring body set up by the Forest Bench of the Supreme Court to look into forest and environment issues. This and two other applications drew attention to the allegedly murky nature of the clearances and highlighted the "horrific ecological and human costs" of the project. This was the beginning of the crucial legal battle that ultimately saved Niyamgiri.

Samantara reached out to the community through Lingaraj Azad, a trusted local leader, and started mobilizing opinion. He wrote articles, organized seminars, marches and satyagrahas to raise a hue and cry. Alongside, he connected with environmental activists such as Medha Patkar and Vandana Shiva. "Senior advocates Prashant Bhushan, Sanjay Parikh and Ritwick Dutta put up spirited battles in the courts--all pro bono," says Samantara. By then the issue had garnered considerable global attention. Relentless campaigning by non-profits such as Amnesty International, ActionAid and Survival International led to major stakeholders pulling out of Vedanta Resources Plc, vindicating the anti-mining groups. The Norway Pension Fund and the Edinburgh-based Martin Currie were among them.

In 2006, the annual general meeting of Vedanta is about to begin in London. After buying a few shares of the company, campaigners from ActionAid enter the large boardroom packed with shareholders. They hand out material to them, at the entrance, that piece together the community's version of the story. "Our aim was to expose the shocking environmental (the refinery is seriously polluting, leaving people sick) and human rights violations (forced land acquisitions) in Lanjigarh and Niyamgiri," Bratindi Jena of ActionAid recalls.

In November 2009, Edward Mason from the Church Commissioners for England, another major investor in the mining project, visits villages at the periphery of Vedanta's Lanjigarh refinery and later arrives at a gathering of 150-odd Dongria Kondh. He hears their message to Vedanta, loud and clear: "Leave Niyamgiri. Go away!" Soon the church announces divesting its stakes. They had concluded that tribals in the refinery area had not been treated "responsibly by Vedanta" and was concerned that "people in the mining area would not be treated responsibly either".

Taking on the establishment is never easy. The Dongrias have spent the past decade countering the backlash. A home ministry report suggests that the NSS is a front for Maoists and the locals face rampant "police atrocities and repression", according to Samantara. NSS leader Kumuti Majhi, 63, had been thrown in jail multiple times under "false allegations" and ostracized for being "anti-state". Another leader Lado Sikaka was allegedly tortured and beaten up by the police. Manda Kadraka, a teenaged boy, was shot dead in February last year in the Niyamgiri area, a chilling attempt to silence the resistance, some say.

Samantara's unyielding presence has also been inconvenient for some. He testifies to facing "many attacks, and surviving thanks to the people each time", and occasional attempts to lure him away from his path. But Samantara is proud that the movement has remained united, peaceful and democratic throughout. "We have always maintained a distance with Maoists," he adds. Medha Patkar, a Goldman Prize winner and environmental activist, explains the significance of Samantara's work: "Prafullaji's absolute commitment to non-violence is at once strength-giving and faith-affirming. I see his work as a new form of Gandhism." According to Patkar, Samantara sees environmental justice to be just as important as sustainability. "His major contribution is that he has put the peoples' concerns within the legal and constitutional framework."

The weightiness of all the accolades after his award has not rendered Samantara self-important. Only, he is amused that he has been "branded anti-development". "I have a problem with the development model where ecological concerns are ignored and people are uprooted and thrown away from their habitats. This simply creates new poverty zones in the country," he says. Out of the most backward districts in India, a large proportion is from mining zones that are inhabited by the poorest and most marginalized people.

Samantara points out quite simply that Adivasis cannot be seduced with money or belongings. Their value systems are entirely different, centred around nature and human dignity. "We need an approach that focuses on consultation and consent rather than coercion. Adivasis should be empowered to use forest products for self-reliance and sustainable development along with health and education. Bulldozers must not crush homes, hopes and dreams."

The LSA quotes a study to estimate that out of the 60 million-plus people displaced by all such projects including big dams in India, more than half are tribals. It is also projected that by 2020 this figure will grow significantly. Samantara strongly advocates limiting consumption and determining the extent to which resources can be sacrificed. "This fight is for the next generation, to keep the planet safe from the impact of global warming."

The most exciting part of the Niyamgiri battle for him has been the referendum ordered by the apex court in 2013. Samantara had, in fact, pointed to the Forest Reserve Act that recommends the consent of the gram sabhas in decision-making. "We were worried about the outcome as the government allowed only 12 out of 112 villages to take part. However, everyone spoke in one voice to save the forest," says a smiling Kumuti Majhi. In January 2014, the Ministry of Environment, Forest [and Climate Change] decided to debar Vedanta from mining in Niyamgiri. As news of their victory reached the villages, the hamlets erupted in drumbeats, dance and music.

Vedanta, meanwhile, has maintained its commitment to social responsibility. In a statement the company says: "On 9 May 2014, we made a public announcement that Vedanta will not be seeking to source bauxite from Niyamgiri hills without the consent of the local communities and are committed to it." Also, that the Lanjigarh refinery "has no potential impact on indigenous people and vulnerable tribal groups."

The company highlights its philosophy of 'working together, growing together' with the local communities based on 'conversation', 'collaboration' and 'creation of shared value'. Vedanta is proud of its robust sustainable development initiatives--health, education, environment protection, alternative usage of waste and creating sustainable livelihoods--for the communities in Lanjigarh.

Today Samantara is grateful for everything, most of all the support of his loved ones. "I am incredibly lucky to have met my wife Usha who has stood by me throughout. I've never earned anything all my life," he says. His father, 91, and mother, 86, do not quite grasp the details, but know he works for the people and are very proud of him too. "I haven't given them much, but I have got lots of love."

His campaigns have been run thanks to the contributions and generosity of people who support his work. Samantara's friends and family are worried because of the two cerebral strokes he has suffered in recent years, but he brushes it off. "My work is not done, we must fight to stop the refinery in Lanjigarh that is destroying lives, not to mention other such natural resources of our country," he says.

Human connections inspire and energize him. Samantara is thrilled to have connected with farmers and indigenous people from different parts of the world. "People are the same everywhere, so are the tools of oppression. I believe together we can achieve the globalization of people's movements," he says.

At a packed auditorium in San Francisco on Earth Day, Samantara accepted the Goldman Prize, invoking Mahatma Gandhi: "The world has enough for everyone's need, but not enough for anyone's greed." And the audience broke into applause. This prize to him is a rare recognition of the struggles of the disenfranchised. "I feel hope," he smiles.

TIMELINE

June 2003: Vedanta Group signs MoU with the Odisha government for the construction of an alumina refinery in Lanjigarh and an open-pit bauxite mine in Niyamgiri.

September 2004: MoEF grants environment clearance for the refinery.

November 2004: Biswajit Mohanty of the Wildlife Society of Orissa files an application against Vedanta before the CEC of the Supreme Court (SC). Samantara and Delhi-based geologist, R. Sreedhar, file two other applications. In December the CEC sends a fact-finding team to the region.

September 2005: CEC submits a scathing report to the SC. It recommends revoking the refinery clearance and a ban on mining in Niyamgiri.

November 2007: SC bars Vedanta from undertaking the project. Invites Vedanta subsidiary Sterlite Industries to resubmit proposal, mentioning safeguards.

April 2009: Despite protests, environmental clearance is granted to Sterlite for mining operations.

June 2010: MoEF orders a panel to evaluate the mining aspect. In August the panel suggests against giving it permission, also that government takes action against Vedanta. Vedanta appeals.

July 2011: MoEF revokes Vedanta's mining clearance. The Dongria Kondh welcome it.

April 2012: SC hears Vedanta's appeal against the mining ban.

April 2013: SC rejects appeal; orders referendum in 12 Dongria Kondh villages.

July-August 2013: All 12 tribal villages, out of 112, vote against mining.

Jan 2014: MoEF rejects the mining project in Niyamgiri.

February 2016: The Odisha government files an interlocutory application before the SC to conduct fresh gram sabhas, which is turned down in May 2016.

PADMA'S STORY

Tribal Odisha is a crucible of hunger deaths. In 2005, 18 children died in Nabarangpur near the Chattisgarh border. Heartbroken and angry at the tragic loss of innocent lives, Samantara rushed there. On his way back he noticed a small, emaciated child and stopped. Three or four years old, she walked along the river, half-clothed. Still hurting from what he had seen and heard, Samantara bent down and asked the girl her name. "Padma," she whispered weakly. He took a photograph of the child before he left. Later he looked at it, wondering how the Padmas could be saved.Samantara never quite forgot her. In 2008 he wrote the book Padma's Tomorrow, a sharp indictment of poverty and death. Her image from that day was on the cover. When he returned to Nabrangpur in 2012, he was thrilled to see Padma a happy child, studying in the sixth grade. That day, he opened a fixed deposit account with Rs 10,000 in Padma's name (the money was from the sale of the book he wrote) and pledged to sponsor her education. Today she is in class X and Samantara can't wait to share a bit of his prize with her.