- HOME

- /

- Culturescape

- /

- Book Extract

- /

How My Interaction With A Naxal Leader Changed The Way I Looked At Naxalites

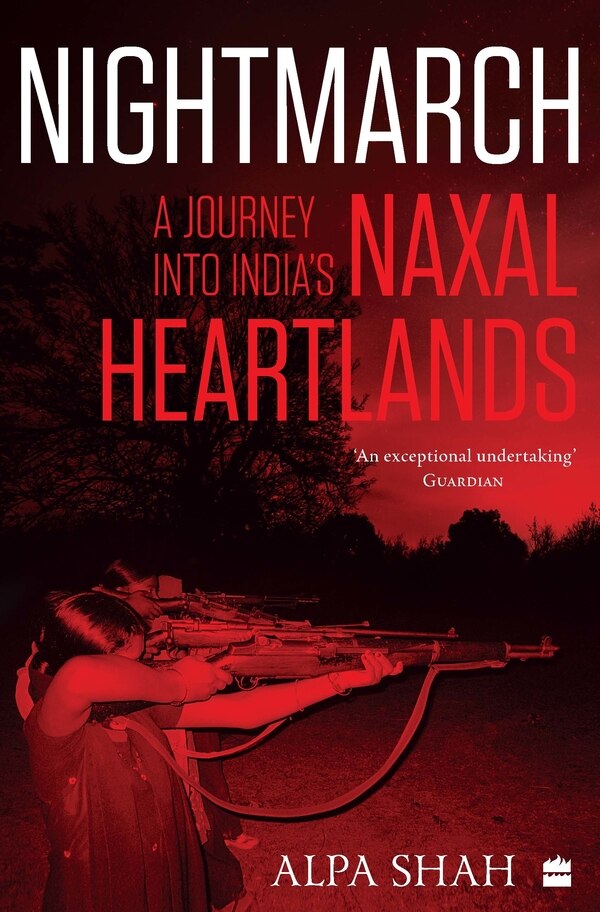

Between 2008 and 2010, anthropologist Alpa Shah spent 18 months in Jharkhand trying to understand what drove the Naxalite movement in India. Her immersive experience of living amongst tribal people, adivasis and Naxal leaders and cadres led her to write Nightmarch, a sensitive and balanced account of the Naxalites in India.

The rules of marching had to be learned fast. Always walk in single file. Keep the gap between you and the person in front of you as small as possible. Follow the orders of the Platoon Commander. The platoon was divided into three sections, each with a Section Commander. Follow your Section Commander and stay with your section, even when you sleep. Keep your weapons by you, ready for action at any time.

Everyone, except for me, had a gun. Three AK-47s, some INSAS rifles, several .303s, some Sten guns and the rest police rifles. They had all been stolen from the police, as was the case with most of the Naxalite weapons. The lead section, Section A, had the best weapons and soldiers, and was to fight in the event of attack while Section B, which housed the leadership, would retreat with Section C. I was in Section B with Gyanji, his bodyguard and Kohli.

Communication from one end of the platoon to the other took place via designated runners. Section Commanders carried walkie-talkies but their use was restricted to emergencies for fear of interception by the security forces. At the front of the platoon, a scout who knew the route was to lead. Bringing up the rear, a sweeper brushed away footprints, erasing the traces of our presence on dusty or muddy paths.

I was told more rules: At the beginning and end of each stage of the journey, pay attention to the roll call. Know the rendezvous point – RV for short – for the next stretch of the march, should we lose each other. At night, when it was difficult to distinguish friend and foe, always use the code questions when approached by anyone. For the first night, it was: “Who are you?” The response, “I am a Shankar. Who are you?” To which the reply was, “I am Krishna.”

After walking for two hours, we stopped on a hillock outside the village where our Section Commander had grown up. Like Prashant, he was from a family of small farmers who had once been cowherds and went by the surname Yadav. In the 1980s the Naxalites had driven away the high-caste landlords who owned large tracts of land from this village and redistributed their lands amongst small farming families like that of our Section Commander. The village was therefore full of people whom the Naxalites could depend on, which is why the guerrillas considered it a ‘safe’ zone.

Gyanji said the area we were in was also safer than the terrain that lay ahead because we were by the border between Bihar and Jharkhand. Borders were regularly used by the guerrillas to evade the security forces. If chased by the police from one state, they crossed over into the next state to escape further pursuit. The state police forces rarely coordinated with each other and it was unlikely that the Bihar police would cross into the territory of their Jharkhand counterparts or relay information in time for the Jharkhand police to intercept the fleeing guerrillas on their side of the border. Such inefficiencies and lack of coordination amongst the ruling elites must be used to guerrilla advantage, said Gyanji.

Although it was a ‘safe’ area, following guerrilla best practice, we waited for darkness to engulf us before descending into the village for our dinner stop. The sky was full of bulbuls, starlings and thrushes fluttering and dancing in the air in circles, chirping loudly before they returned to their nests for the night. Soon after, bats flew out of their roosts, their darting and sharp manoeuvring markedly different from that of the birds. When smoke was rising from most of the huts as their hearths were lit, we climbed down.

Two ‘runners’ from the platoon had been sent ahead to request one plate of food from thirty different houses in the village. It felt strange to be at the receiving end of this hospitality. Over the previous year, in Lalgaon, I had become used to taking a plate of rice to the guerrillas when they stopped by with no time to cook for themselves. Somwari, the Oraon tribeswoman in whose house I lived in Lalgaon, and whom I called my ‘sister’, insisted that the plate was heaped so full that rice fell off it. She said the boys would be tired and weary and needed to eat well. We gave them a share of whatever we had cooked for ourselves: rice and usually one other preparation as accompaniment. Perhaps a lentil dal, a spinach broth, a tomato chutney, or, if there were vegetables, some curry made from those. Once in a while, though, would come a day when we had only a green chilli with salt to spare.

The platoon broke up as everyone dispersed into the village to eat. I retreated into the foyer of a house with my bodyguard Kohli and our section. Staying in the shadows, I followed the rules we had agreed upon to draw as little attention to myself as possible. But Kohli and the young men who were looking after me found it difficult to remember that I was supposed to be a man. “Didi, are you okay?” they asked. “Didi, can I fill your water bottle? There is a hand pump here,” they said.

A decision had to be taken about how far to proceed that night. To continue much further would have meant leaving the safety of the forested areas and of the border zones, and marching across the exposed agricultural plains, across a busy highway, and traversing more rice fields before safer territory could be reached again. The journey would take another six hours. Perhaps eight.

I felt everyone’s eyes on me, wondering whether I would make it. Would I last the whole journey? Gyanji had carefully plotted all the points at which I could safely be sent out, transiting from ‘underground’ to ‘overground’ by motorbike or bus.

I thought about what I knew of Gyanji’s own physical challenges. He was an intellectual with an agile mind but his body was not made to trudge through the forests of eastern India. Although he never talked about it, over the course of the time I had spent with him, I discovered that he suffered from a sharp abdominal pain. I had seen him collapse flat on the ground in the middle of a meeting of guerrillas, gasping to recover from the pain. Kohli said that it was a gift born of his inability to eat on time, to get two meals a day.

Years of wearing the polyester olive-green uniform in the sweltering heat without washing for days on end had given Gyanji an itchy body rash. Sometimes there was no time to wash for eight days in a row, he had confessed. Two days ago, I had overheard Bimalji trying to convince Gyanji to give up the uniform and wear cotton pyjamas in the platoon. But Gyanji insisted that he did not want treatment that privileged him above the rest. I had also learnt that he suffered from a bad ankle. After several hours of continuous walking it would simply give way and make him fall.

Thinking of Gyanji’s fortitude despite all these ailments made me determined to walk the whole way, to try not to falter on a single step, and not be the reason for any delay. I told Gyanji I was prepared for what lay ahead. He raised his eyebrows at me. I could feel his eyes gently asking me whether I was sure. But he turned around and told the Platoon Commander we were ready to go.

As it turned out, the Platoon Commander, Vikas, was not ready himself. Of the Platoon Commanders I had met, he was the one I liked the least. I had come to think of him as ‘the interrogator’. The first time I had met him was one night six months into my stay in Lalgaon, when, with a different platoon, he passed through the hamlet where I lived. I took a plate of rice and spinach from our house to the bamboo grove where his platoon was resting, curious to see them as they were said to have come from afar.

When they had eaten, he returned my visit by sending two of his armed guards to Somwari’s house where I lived. They led me back out into the village and to a nearby disused room with crumbling walls where Vikas was waiting in a dark corner, sprawled out across an old charpoy. Arrogantly throwing questions at me, he asked who I was and why I was there. He appeared to have no interest in my responses and instead went on to talk at me, recounting stories of spies who had entered the forests but were never seen again. “Do you know what we do to them?” he asked. “We cut them open and throw them in the gutter, pumping their bodies with bullets till they look like a sieve.”

When he let me go, I tried not to reveal that I was shaking even though I knew it had been just a show of power. A few days later, when more senior leaders called me to the guerrilla camp in the forest where he was staying, he looked down at his feet and blushed. But I was left with the bitter taste of that first meeting in Lalgaon.

Everyone was now ready to march on and cross the flat rice fields, but Vikas argued it would take several hours for all of us to be fed. He said it would be 10:00 p.m. before we could continue the journey again. We would reach our destination only by four in the early morning provided we walked non-stop all night. Vikas persuaded Gyanji and the Section Commanders that it was not a good idea to persevere that night.

We found a grassy area with several mahua trees to rest under, a half-hour walk from the village. Although I knew that a mahua tree had many uses – wine was distilled at home from its small yellow flowers, cooking oil was pressed from its seeds – what I did not know was that the Naxalites considered it to be the very best to sleep under because its large flat leaves trapped the air beneath it, preventing the daytime warmth from escaping into the sky at night.

Sleeping positions under the trees were mapped, sentry rotas agreed. Mats and blankets were rolled out. While some of the soldiers tossed them out hastily, Gyanji took great care to clear the patch of earth on which he would sleep, laid out a mat, and stretched a pressed bedsheet perfectly across it. A very luxurious bed, he joked. No matter how rough or rudimentary the conditions, it was still possible to differentiate degrees of comfort.

The author

The author

He was not what I had expected of a leader. Although he could be firm, Gyanji was soft-spoken, had none of the oratory skills of other charismatic leaders, was of small build, and had a quiet and almost reticent demeanour. Even though he considered the war against the state and the need to train new soldiers necessary, it seemed to me that he was uninterested in the techniques of making landmines or in the plots to loot guns. He would rather watch the dance of starlings and read late nineteenth-century European and Hindi-Urdu poetry, short stories and novels, alongside Marx.

There was soon a chorus of snoring men around me. Somebody was complaining that his neighbour had selfishly cocooned himself in the one blanket they shared, without leaving any cover for his freezing friend.

I had too many thoughts to be able to sleep. The moon was very bright that night. It made me pensive. What were the emotional costs of living underground for a leader like Gyanji? With Kohli and Gyanji’s bodyguard asleep between us, I told Gyanji that I could never contemplate joining them. It was not just the difficulties I had with the cycles of violence they were caught up in. Nor was it just the question of whether their methods and programmes were appropriate or not. The first and insurmountable barrier was that I could not withstand leaving behind my beloved family and not seeing them again. I could never break their hearts, I said.

I didn’t ask how his children lived with a big question mark about who their father was. There were many families in India where the man would send money home from Dubai or Doha and visit his loved ones only once a year. However, this migration is perhaps easier for a child to comprehend when compared to having a father who had taken up armed struggle in the wilderness in the heart of the country.

Gyanji, I could see, was staring at me, but I could not read his thoughts until he spoke. “Don’t you think that we all have the same concerns?” he asked. He had not seen his mother for the last two years and even if he wanted to, he could not. He said, “Do you know, I’ve been told she is so worried about me that she cries herself to sleep every night?”

A little agitated, he continued, “You know our wives, many of them live like widows. Do you think we haven’t broken all of their hearts?”

I felt remorse for what seemed to be an insensitive reflection on my part. Gyanji carried on and he told me about his best friend Paresh, killed in an encounter in 1992, and of the pain of visiting Paresh’s mother who could only see in Gyanji a reflection of her son. He told me about Nimesh, another close friend, who in 1999 went in search of his kidnapped fiancée and fell into the trap of a gang sponsored by the state. The gang made him watch his beloved being raped, before killing them both. Gyanji said he went to visit Nimesh’s mother at their mansion in a wealthy suburb of Delhi to find that, after the murder of her son, she had become both deaf and dumb.

By the time I met him, Gyanji had been underground for more than twenty years. As a young man, he had more or less broken off links with his parents and siblings to create a new family with the rebels underground. Many young guerrillas – men and women – turned to him as a pseudo-father. He was reputed to be kind and gentle but also firm and derived immediate respect from those he came in contact with. I was already so used to seeing him as a father figure in the underground army that it was easy for me to forget that it was at the cost of him breaking ties with his own family.

Gyanji soon joined the discord of snoring men. But I lay awake, gazing at the dark patches on the moon, reflecting on the things I had learnt about him.

A phone was ringing. I had been drifting off into sleep but was jolted wide awake with the sound. Its shrill tone seemed so out of place amidst the silence of the night that it made me tense. It was late, perhaps past midnight. Who could be calling at this time? Usually there was no phone reception in these areas and one had to climb hillocks or ask the local people from where the network of a distant cell phone tower could be accessed. Moreover, we were under strict instructions not to use our phones during the march unless absolutely necessary for they could be intercepted or tapped or triangulated by the Indian police; it was an easy way for them to know our whereabouts.

The phone abruptly stopped ringing and I heard Gyanji whispering that he would call back. I watched him get up and disappear into the distance. Who was it? Whom did he need to call at this hour? But I didn’t like to ask.

The night was so clear and the sky so bright that I could see Gyanji’s silhouette pacing up and down on the dark outline of the nearby hillock. Clearly something was up, he seemed to walk faster and faster. Five metres paced in one direction, five metres the other way, back and forth, again and again.

He returned after what seemed like an eternity. His shoulders were slouched; his upright bearing and customary poise had disappeared. From within my sleeping bag, I whispered to ask if he was okay.

It was his wife, he said to me in English, clearly not wanting the others to hear him. She was crying because their son was having trouble keeping up with classes at school. She wanted him to go out of the forests to meet them. He could not do that. They had had an argument.

I was surprised. I knew that Gyanji was married. He had told me that his wife was a ‘Professional Revolutionary’ too. But ‘going out’ meant going ‘overground’, away from the protection of the forests and the underground army. It was a lot to ask.

Gyanji was a highly wanted man. The police had promised a reward for anyone who brought him in. Rs 1 lakh in cash. Special security teams had been developed with the specific aim of hunting him down. Gyanji said that arrested comrades had, under torture, been interrogated for information about him and had a recording of his voice played back to them. Athough the police had somehow managed to get his voice recording, they did not yet have a picture of him.

“I thought she was with you, with the Naxalites,” I said.

She was once, he said sombrely, but she had left. It had been against his wishes, but she was determined to support their three boys and give them a better and more stable upbringing than what they could provide with a nomadic lifestyle. Now he rarely saw any of them, except very occasionally, perhaps once in six months, whenever they could arrange to meet in a safe house in a small town or when she was able to come and visit him in a jungle where he was based. However, as the security forces grew stronger, it had become increasingly dangerous to make the passage from ‘underground’ to ‘overground’.

Settling back under the blanket between his bodyguard and Kohli, he said he didn’t know what to do because they were under strict instructions not to venture out of the safety of the underground armies. I could hear the anguish in his voice. He fell silent and I could sense his retreat into something deep within him. I didn’t know how much more to ask and then heard his soft snoring.

“Chai?”

It was still dark, but I looked up to find Gyanji standing next to me, holding out a stainless-steel beaker full of piping hot syrupy-sweet tea.

“Five-star treatment!” I groaned, climbing out of my sleeping bag and rolling it up. The milk smelt like honey.

“It’s my only weakness,” Gyanji confessed with a mischievous look in his eyes.

He was clearly in a better mood and had slept well. I, on the other hand, had kept thinking about his wife and what it must be like to be married to a man you rarely saw and could not discuss with friends and acquaintances, who would not be around for your children when you needed him. Would Gyanji indeed break the rules and leave the forests for her? Was his need for tea the only weakness that Gyanji felt he had?

Extracted with permission from Nightmarch: A Journey into India's Naxal Heartlands by Alpa Shah, published by HarperCollins.