- HOME

- /

- Better Living

- /

- Family

- /

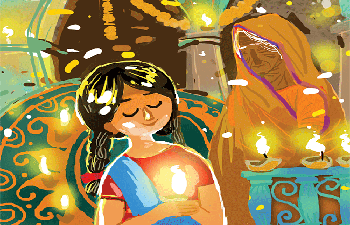

My Forever Diwali

A bittersweet tapestry of emotions and memories to light up every heart

Diye aa gaye, Mataji; kahaan rakhne hain? (The diyas are here; where should they be kept?)

As a little girl growing up in a large sprawling kothi (mansion) in Agra, with my grandparents, uncles and two splendid German Shepherds for company, I would wait to hear this all-year round. It meant that my favourite festival, which heralded the winter, and a new year, was around the corner. It meant that my beloved storybooks, in which I had my nose buried all my waking hours, would have to be set aside for a while, but for once I wouldn't resent the interruption. It meant that I would have to hunker down and get the diyas all prepped for the lighting. That was a ritual I loved, and it was my responsibility.

Of course I had help. A couple of family retainers were around to lift and fetch and carry. But I helped wash them, stack them in rows and waited for them to dry, just enough. 'Mataji' presided, but left me largely to my gleeful devices, and I had a field day. Days, actually, because the process took a great deal of time, and everything had to be ready by Chhoti Diwali (the day before Deepavali).

Mataji was my naani (maternal grandmother), the matriarch who ruled over her household with benign imperiousness. My naana (grandpa) was a martinet, stern and upright, and he demanded instant compliance: I learnt, very young, the lesson that falling and crying is of no use; get up, dust yourself off and carry on.

This is not a digression. It has something to do with what I am about to tell you about my long-ago Deepavalis, and how I was expected to contribute to the festivities, which began a full month before. I learnt that all tasks were important and, even more crucially, doable: No one was allowed to throw their hands up and say this or that was too difficult, or impossible. These days, it would be called tough love. But for me, it was what it was. And I was content.

Looking back, I wonder how as a six- or seven-year-old, I happily washed hundreds of small mitti diyas (made out of clay), their plainness speaking of a beauty we don't see anymore, in these days of painted, varnished, curlicued, designer ones, colourful candles and those hideous strings of bulbs. If I were in my grandparents' place today, would I assign this task, or something similar, to such a young one? Something that required a great deal of hard work, concentration and no slacking? Maybe not. But maybe then, the today me would be a very different person.What I imbibed, without being told in so many words, is that in a family, you pitch in, old or young. You ask for help if you need it, but you also learn to problem-solve, old or young. In the kind of household my grandparents had, where things were easy, I could have grown into a brash, entitled brat. But my diyas, and other things that required a similar ask, made me learn how to lean in, before the phrase was a phrase. It made me learn how to help, how to be around, how to grow towards the light.

The washing of the diyas was imperative. Because they needed to be a little damp when the mustard oil was poured, carefully, just a little over the halfway mark. And then we would slide in the wicks, made out of cotton wool (the job of my aunts and grandma) carefully, the tip oiled just enough to catch the spark: Too much and it would burn too quickly; too little and it wouldn't light at all.

A perfect wick, like a perfect diya, its outside glistening with oil, is a thing of beauty. In my speeded up Deepavali celebrations these days, I insist on having at least one diya filled with kadwa tel (mustard oil), its flame flickering gently, the smell of the oil permeating the agarbatti and the camphor of the puja thali, the smoke spiralling upwards to the freshly whitewashed walls.The annual tradition of doing safedi (whitewashing your house just before Deepavali) would lead us into autumn. The days got shorter, the harsingar (night-flowering jasmine) in the garden flowered, and the chameli beds began to glimmer.

The tailor master would arrive, and our old reliable Singer machine, which had foot pedals, would be brought out and oiled. Deepavali would also mean new clothes, and I would wait for the inch tape to tell me if I had grown any taller. But the vertically challenged me would have to get used to the kindly gent tut-tutting, licking the end of his pencil stub and writing the same measurements all over again.

And then Deepavali would almost be upon us. The halwais (confectioners) would come home, set up massive stoves and other implements in their allotted corner, and start making boondi laddus. The melt-in-the-mouth laddus would be packed in boxes, to be sent to family and friends, and a separate batch would be made for the puja.

All the neighbouring kothis would be busy doing the same thing. Coming back from school, we could smell the whitewash, and by evening, a distinct nip in the air. The holidays would begin. Satchels would be put away. By Dhanteras, the auspicious day when you bought bartan (utensils) and metal, the fun would have begun in all seriousness.

Heaps of kheel-batasha (a form of prasad) would be arrayed in deevlas (containers), and puja thalis would be readied: long strings of fat orange-and-yellow genda phool (marigolds), fresh fruit, boondi laddus and camphor on a betel leaf. My aunts would draw the rangoli (wholewheat flour and red alta lines) around the puja chowki. We would all gather, in our sparkling new clothes, and the pandit would conduct the puja. With the collective chanting of 'Om Jai Jagdish Hare', and the aarti (praying with a lit lamp), which we would take turns doing, it was time for patakhas (fireworks) -- mostly phooljhadis (sparklers) and rockets, and yes, those awful noisy string 'bombs' (there was no notion of firecrackers being evil or environment-polluting those days), which I invariably closed my ears to, sitting with the trusty dogs Ruby and Tiger, waiting for the ruckus to die down.

No feast without feasting, of course. Hot fluffy puri; khasta kachauri; boondi raita; zesty aloo sabzi, just runny enough; khatta-meetha kashiphal, pumpkin of the lip-smacking kind I've had nowhere else; and mithai. And then, teen-patti (Indian poker), another ritual, without which no Deepa-vali would be complete: the sparkling white sheets, new packs of cards and the stakes as low as five or ten paisa for us kids (it was a little higher for the adults). It was not the intense gambling it's become now, it was about welcoming Goddess Lakshmi home.

And celebrating the return of Lord Ram from his vanvas (exile). I firmly believed he, Sita and Lakshman would be helped by seeing the lights from far off: the rows and rows of diyas, hundreds of them -- starting from the steps of the veranda, all the way up to the terrace in our house -- could be seen from a distance. The glow, that pierced the darkness, lasted through the night.

And a few shone until the dawn.

Shubhra Gupta is a well-known film critic and author of 50 Films That Changed Bollywood, 1995-2015.